In Times of Perseus

Curated by Sophie Landres

March 16 – April 22, 2018

In Times of Perseus

Curated by Sophie Landres

March 16 – April 22, 2018

I know we’re all afraid. But my father told me: Someday, someone was gonna have to take a stand. Someday, someone was gonna have to say, “enough!” This could be that day. Trust your senses. And don't look this bitch in the eye. - Perseus in Clash of the Titans (2010)

Sargent’s Daughters is pleased to present In Times of Perseus, a group exhibition curated by Sophie Landres. The exhibition will open on Friday, March 16th, from 6-8pm and be on view through April 22nd, 2018.

In Times of Perseus explores parallels between contemporary art practices and the myth of Perseus and Medusa. Whether finding analogies for art making in the story line or transvaluing its familiar symbolism, the featured artists tap into a zeitgeist full of venom, petrification, dazzling illusions, and weaponized reflections. Hair weaves through the exhibition as filaments of expressivity. The aesthetic is electrified, fetishized, or symptomatic of social poison. Where Perseus’ shield became Medusa’s self-defeating mirror, here reflections obliterate the subject while eyes glisten and avoid contact. Transmutations into stone or into spectra suggest ways to escape the body, mind, or myth.

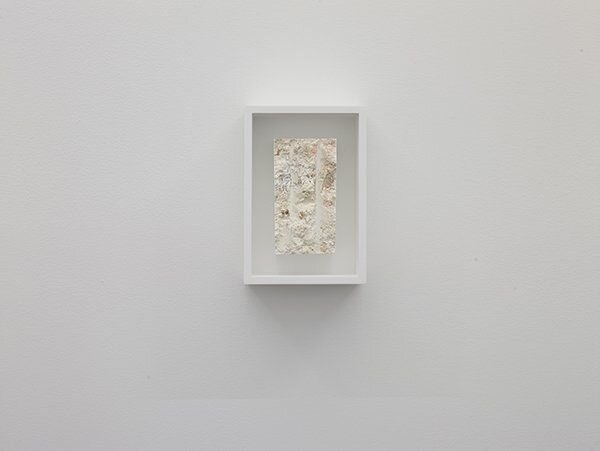

Zarouhie Abdalian converts tools made for breaking stone into a mirror that warps shards of the viewer’s reflection in Joint (i) (2016). Her hydrocal relief casts are taken from an abandoned Mississippi chalk mine. Their chisel marks and traces of pale color index the manual labor of past miners and trespassers who aestheticized the walls with graffiti. A non-figurative and anonymous group portrait results.

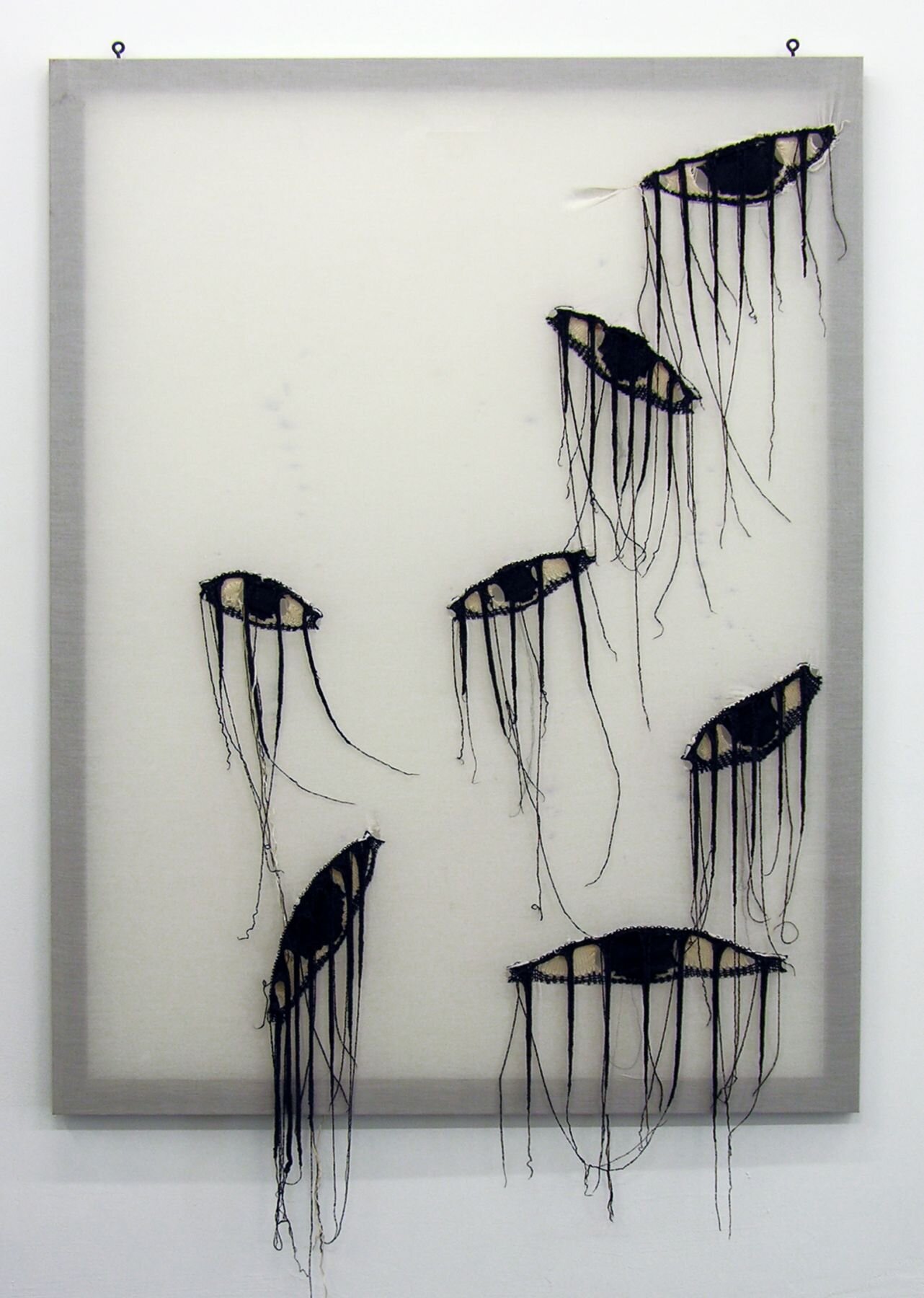

Drawn with tangles of black thread, the eyes in Liz Collins’s Crying (2010) have lashes like tentacles that seem to weep or weave into and out from the canvas. The thick strands of Veins: Darkness (2018) are tied bondage-like to a steel frame, resisting the force that restrains them.

Layers of Ala Dehghan’s mixed-media installation Triple Action/Tear Production/Hydrophobic Effect (2017) build into a poetic system designed to reorient the viewer’s perception and sense of self. Vibrant strata of fabric and transparencies interface with collages depicting Artaudian personae. As the viewer moves, these thresholds become conduits for visualizing different dreams, politics, bodies, and memories.

Brock Enright’s work deals with artificial intelligence, the logic of chaos, and extreme corporeal experiences. In Tin Man (2016), a head rests on a bed of raked poppy seeds, ambiguously invoking a Zen garden, slumbering addict, or automaton pulsing with the desire to feel more. Conflating the agility, sexual cannibalism, and empathetic brainpower of animals, the spindly limbs of Mantis (2016) appear bandaged and topped with a triumphant fuchsia dolphin head. Other eyeless figures oscillate between ecstatic and melancholic airs.

Typifying Zipora Fried’s distrust of literal meaning, Good luck happens to a lot of people (2017) is explicitly not about hair. And yet, its fluid pencil marks are rendered in sweeping movements as if the artist was brushing the very hair she both conjures and disavows. Forever D (2018) marks a new series of sculptures derived from ink drawings that imagine mythic struggles between mysterious beings.

Sarah Meyohas’s “Speculation” photographs (2017) configure two-way mirrors into dizzying mise en abymes that obfuscate as much as they reflect. Reminding us that conjecture, observation, and venture capitalism are all forms of speculation, she illustrates the feedback through which economies of desire, visuality, and finance operate. Bound in serpentine ropes, Rope Speculation ominously precludes any glimpse of a human subject.

Shoplifter’s series of melted tyvak “Comets” (literally “long-haired stars” in ancient Greek) mimic the formation of igneous rock. Printed with hair and adorned in crinkled silver jewelry from the artist’s capsule collection, they could be the remains of women overtaken by lava or celestial bodies anthropomorphized as they hit the earth. By also calling to mind men who glimpsed Medusa and the Icelandic lore that sunlight turns trolls into rocks, the sculptures intercross myths in which illumination has a dangerously fossilizing effect.

Daniel Subkoff’s recent work considers the consciousness of stones, crystals, and petrified wood. The hypnotically vibrating lines in Petrification Trails (2017) emulate the steady accumulation, chance occurrences, and extended time of mineralization. Substituting for pigment in The Face of Space (2017), rocks and minerals hang from a tilted canvas. Appearing to float yet acquiescing to gravity, they evoke the disorientation and tranquil stillness of meditation.

Through science fiction fantasy, Saya Woolfalk reckons with the utopian and dystopian implications of cultural hybridity. Untitled #6 (2015) depicts a figure transformed by “ChimaTEK,” an extract of luminescent rock energies produced by genetically shape-shifting women/plant beings. In Color Mixing Machine 1, 5, & 6. (2017), morphological technology is used to counter racist, ethnocentric, and sexist subjectivity formation.

Sophie Landres is a curator, art historian, and professor in the Arts Administration program at Teachers College, Columbia University. She is currently completing a manuscript on how Charlotte Moorman and Nam June Paik adapted musical motifs to contest social and compositional control over performing bodies.